Tulips have become an almost expected sign of spring – their bright colors and bold blooms a welcome change after a long winter. You may be surprised, however, that these plants are not as simple as they seem.

Tulips in their Native Habitat

Those most familiar with tulips for their widespread cultivation in Holland may be surprised to hear that the genera does not appear in Western cultivation until the mid-16th Century - relatively late, in the grand scheme of things. Tulips are thought to be native to Asia Minor, the Near East, and the Mediterranean, where they can still be found growing on mountain slopes and steppes. These tulips look quite different from the ones you’d see in most gardens today – they’re often smaller, with interestingly-shaped flowers – petals are often pointed and smaller, thinner leaves. Most modern tulips – which hold the taxonomy Tulipa x gesneriana – are thought to be descendants of Tulipa suaveolens, a red flower native to Crimea which sultan Selim II loved so much that he had 30,000 bulbs brought for his palace gardens.

![[Img 1]Tulipa variegata (1772-1796; Magdalena Bouchard)](https://www.masshort.org/hs-fs/hubfs/%5BImg%201%5DTulipa%20variegata%20(1772-1796%3B%20Magdalena%20Bouchard).jpg?width=551&height=800&name=%5BImg%201%5DTulipa%20variegata%20(1772-1796%3B%20Magdalena%20Bouchard).jpg)

An illustration of “Tulipa variegata” in MHS’ archives, painted by Magdalena Bouchard in the late 18th century. This likely shows a variety of Tulipa clusiana, a species native to the Himalayas.

The first recorded mention of the tulip in all of human history comes from the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, a book of poetry likely written in the late 11th or early 12th century. Similarly, the first images of tulips comes from tiles excavated from Kubadabad Palace, a former summer residence in Turkey which dates to the 1220s-1230s. This doesn’t necessarily mean they weren’t cultivated before then, just that no earlier records survive. Indeed, tulips were incredibly important throughout the cultures of its native range – it’s been hypothesized that this is due both to the flower’s ubiquity in native landscapes and to its Farsi name, laleh (لاله) using the same letters as Allah.

First Image: A tile from Kubadabad Palace held in the Karatay Madrasa Tile Work Museum. Tiles from this palace show the first visual representation of tulips. Source: Dick Osseman. Second Image: An Iznik tile dating to the 1570s-1600, in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. See the species tulip in the center.

The tulip was incredibly important in the culture of the Ottoman Empire – it was frequent imagery on everything from pottery to tombstones to prayer mats – and remains so in its former range. Look close at a map, and you can find place names such as Laleli (place of the tulips) – now the center of Istanbul’s textile trade, but which once may have bloomed with flowers.

Species tulips on an Ottoman tombstone in Istanbul. Source: Lisa Morrow, Inside out in Istanbul

Tulips in Europe

During the reign of Suleyman the Magnificent, the tulip became a national symbol of the Ottoman Empire. Not only did the flower show up in artwork – especially ceramics – but early horticulturists also began the process of selective breeding, leading the way for our modern tulips.

It is during this period that tulips are thought to have entered Western Europe, via an Ottoman ambassador to the Habsburgs, who first recorded used of the word “tulip” in a 1554 manuscript. The earliest known European cultivation is only five years later in 1559, and the flowers were still rare enough in 1565 for a botanical illustration to label one as Narcissus (daffodil).

This invisibility would quickly disappear. In 1590s Holland, Charles L’Ecluse planted the flower at the University of Leiden’s gardens – a leader in botanical innovation – and discovered it could tolerate Northern Europe’s harsh climate. From there, tulips began to spread as a luxury item and status symbol in Holland, due in part to the bright petal colors which was difficult to find in other plants. Trading in tulip bulbs became intensely profitable, leading to a period widely called “Tulip Mania,” which occurred in Amsterdam from 1634 to February 1637. During this period, a single bulb could allegedly go for as much as 12,000 guilders – about the price of a fashionable Amsterdam townhouse.

Most popular in Tulip Mania were those flowers labeled as “Bizarden,” or Bizarres, which featured two colors on a petals in strange, stripey arrangements. While unknown at the time, these strange arrangements are caused by tulip breaking virus, a set of potyviruses. While these viruses do cause unique color patterns, they also severely decrease a plant’s ability to create new bulbs, leading to smaller and weaker flowers over time – until the plant dies off completely.

Most popular in Tulip Mania were those flowers labeled as “Bizarden,” or Bizarres, which featured two colors on a petals in strange, stripey arrangements. While unknown at the time, these strange arrangements are caused by tulip breaking virus, a set of potyviruses. While these viruses do cause unique color patterns, they also severely decrease a plant’s ability to create new bulbs, leading to smaller and weaker flowers over time – until the plant dies off completely.

A tulip with Tulip Breaking Virus at Massachusetts Horticultural Society’s Tulip Mania, 2023. For reference, this flower, if healthy, would have been the darker purple as seen in the image background.

This, in the end, would cause tulip mania to come to an end. Tulips were sold on speculation, meaning folks would buy next year’s bulbs based on the current year’s flowering – for example, buying flowers for the 1636 season in the spring of 1635. When the quantity of bulbs sold failed to materialize in 1637 due to ongoing impacts of tulip breaking virus – combined with the flower declining in fashionability – the bubble burst, and Tulip Mania came to an end.

While the exact extent of Tulip Mania participation is unclear – contemporary scholars think it was likely restricted to a small set of the Dutch elite – it remains a cultural touchpoint, and tulips are, once again, important in the economy of the Netherlands. More than one million people visit Keukenhof Show Gardens to see the tulips every year, and exports of tulip bulbs comprise up to 10% of the Dutch GDP.

Tulips in America

Tulips came quickly to America. By 1642, they were growing in settlers gardens in what is now Manhattan (then New Amsterdam), sent over as a symbol of Dutch imperialism. In 1698, William Penn reported tulips in the palatial gardens of John Tatham, a settler in what is now New Jersey. Still, it is likely that in these early years of America tulip cultivation was limited, with the majority of garden space dedicated to plants needed for subsistence and medicine.

.jpg?width=451&height=567&name=Img%206%20(1).jpg) By the time of the American Revolution, tulips were firmly entrenched in American garden culture – they are mentioned more than any other plant in Thomas Jefferson’s Garden Book, and are featured prominently in portraits by artists such as John Singleton Copley. Early plant explorer John Bartram received tulip bulbs from English plantsman Peter Collinson in exchange for shipments of plants native to the Americas. There is even a carving of a tulip on a quoin at Bartram’s Philadelphia home.

By the time of the American Revolution, tulips were firmly entrenched in American garden culture – they are mentioned more than any other plant in Thomas Jefferson’s Garden Book, and are featured prominently in portraits by artists such as John Singleton Copley. Early plant explorer John Bartram received tulip bulbs from English plantsman Peter Collinson in exchange for shipments of plants native to the Americas. There is even a carving of a tulip on a quoin at Bartram’s Philadelphia home.

Mrs. George Watson (1765), John Singleton Copley. Mrs. Watson was the wife of a wealthy Boston merchant. Everything about her screams wealth, from the fine silk and lace on her gown to the tulips – still a status symbol – in a Delft vase. Her husband imported European goods, which the vase of tulips and fritillaries also indicates.

Smithsonian Museum of American Art.

In these early years, cultivation of tulips – just like with other purely ornamental plants – was limited to a certain class of Americans – usually white, usually men, and usually incredibly wealthy – those with intellectual pursuits, who had time to follow them, and who had the funds and connections to import bulbs to America for their own use. Small pockets of sale may have existed, especially around cities – a newspaper here in Boston advertised fifty varieties of tulip bulbs in 1760 – but cultivation remained isolated. This continued until 1849, when a travelling salesman named Hendrik van der Schoot came to America selling bulbs. The bulbs were a quick sell, especially to the many recent immigrants missing home.

Tulips in a Pot for Forcing, Edwin Hale Lincoln Collection, Massachusetts Horticultural Society.

In the 18th Century, glasshouses were all the rage – those who could afford it might have forced select rare cultivars in pots, such as is seen here.

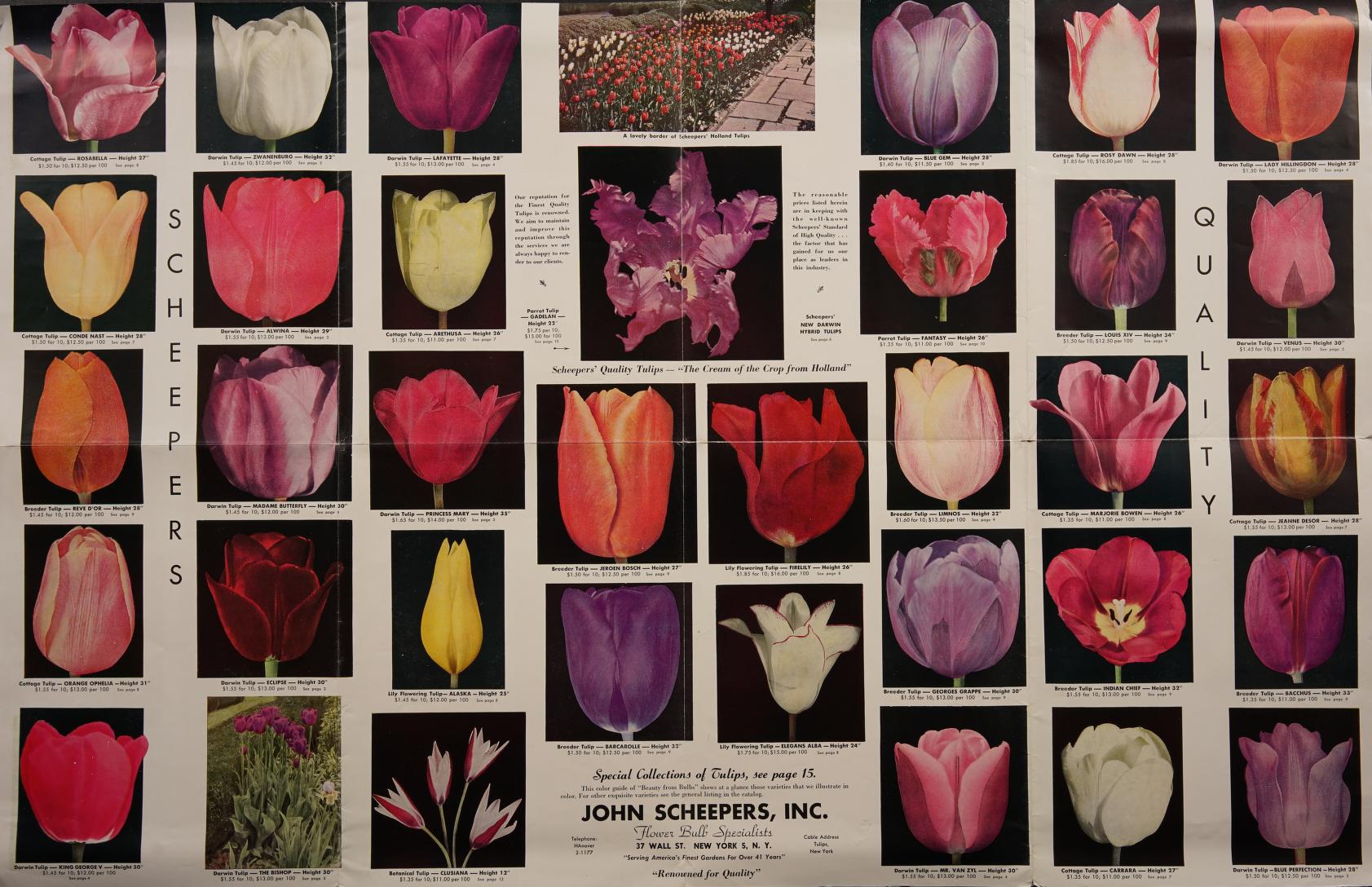

It was an immigrant named John Scheepers, in fact, who revolutionized the American tulip trade. In the process of moving, Scheepers was offered a position as the American representative of a bulb exporter. He eventually founded his own company, whose catalogs – illustrated with lush watercolors, and later photography, published for years in hardback, stood out amongst trade lists. In addition to stock lists, Scheepers would often release marketing materials with planting advice. In 1951, he was the first to introduce Darwin hybrid tulips – the kind you and I are most familiar with seeing – and, along with this release, was an early proponent of mass planting – lots and lots of one kind of bulb, instead of the hyper-curation of specific, rare cultivars. As anyone who has visited a garden (including the Garden at Elm Bank!) recently would know, this idea was revolutionary.

A page from Scheepers “Beauty from Bulbs Color Guide”, 1955 – only four years after the introduction of the Darwin tulip, many new varieties were already on the market. USDA Agricultural Library.

Growing Your Own Tulips

If you want to add tulips to your garden, here are some helpful tips:

- You can buy your tulips now – many places have pre-orders open – but don’t ship until Autumn or Winter – tulips need 12 weeks of cold (at least) to bloom. Plant your bulbs point-up under 6” of soil.

- If you do acquire tulip bulbs in the spring, keep them in a cool-dry place in a breathable bag: hanging them in an onion or orange bag works great!

- Critters really like tulips – make plans to protect them at all stages of growth. We really like chew-proof netting until they sprout, and wireless deer fences or wire bell cloches when they grow above 3-4” high.

- Be prepared to replant bulbs every year – tulips only overwinter about 50% of the time here in Massachusetts!

Here at MHS, we’re big fans of the tulip – it’s a bright indicator of spring after our cold New England winters – and we hope you do too! Be sure to swing by Tulip Mania to see bulbs planted in mass and co-planted with cool annuals to get ideas for your own garden.

Further Reading

If this has piqued you interest, here are some of the resources we used:

- The Tulip, Anna Pavord – A landmark study in horticultural history, this book is worth checking out

- “Tiptoe through the tulips – cultural history, molecular phylogenetics and classification of Tulipa (Liliaceae)”, Maarten J. M. Christenhusz et al, Botanical Jornal – sciencey, but a great source for the early cultivation history of tulips

- Biodiversity Heritage Library – A great source for digitized historic material – check out some historic catalogs!